Planting seeds of mental health wellness in the face of COVID-19 stressors

Under the sun of a summer afternoon, Socorro Balcazar watered a vine drooping under the weight of tomatoes. Like most of the beds in the garden, hers featured tomatillos and chili peppers, all in different phases of ripening on the stalk.

“Without the spiciness, the tomato doesn’t really have flavor, so they combine really well,” said Balcazar, in Spanish, according to Sergio Ruiz, one of the garden’s organizers.

Run by the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), the community garden doubled its typical production during a slow, pandemic summer last year, indicating a local affinity for gardening.

“This just means that they love growing, they love harvesting, and they need access to the land,” said Edith Tovar, LVEJO’s Just Transition community organizer.

Those not tending to their garden beds gathered around long tables under the central pavilion, chatting and playing Mexican bingo.

“We come here to destress. It’s therapeutic to weed and be with nature,” said Little Village resident Gloria Jimenez in Spanish, according to Ruiz.

As the COVID-19 pandemic increased the nationwide prevalence of common mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression, and Chicagoans turned to community gardening to counteract the symptoms.

Common mental health conditions during COVID-19

Studies conducted across the nation over the last year show an overall decline in mental health due to the pandemic’s restrictions.

One in three people experienced psychological distress during the pandemic according to a study released this August led by Elvira Solji and a group of researchers in Australia.

Solji and her team focused on the age-related differences in mental health impacts of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. They surveyed Americans from April 20 to June 8, 2020, asking questions about nervousness, anxiety, depression, loneliness and more to gauge participants’ experiences of moderate mental distress.

The study found that over half of 18- to 24-year-olds reported experiencing moderate mental distress, and that adults up to 44-years-old were most heavily impacted.

In younger adults, moderate mental distress was associated with restrictions to public transit, restaurants, and international travel, while working from home lowered distress rates. Moderate distress in older adults was related to the ban on gatherings of over 50 people and workplace closures.

“The results imply that different approaches are needed both in the handling of mental health and restrictions for different age groups,” Solji said in an email.

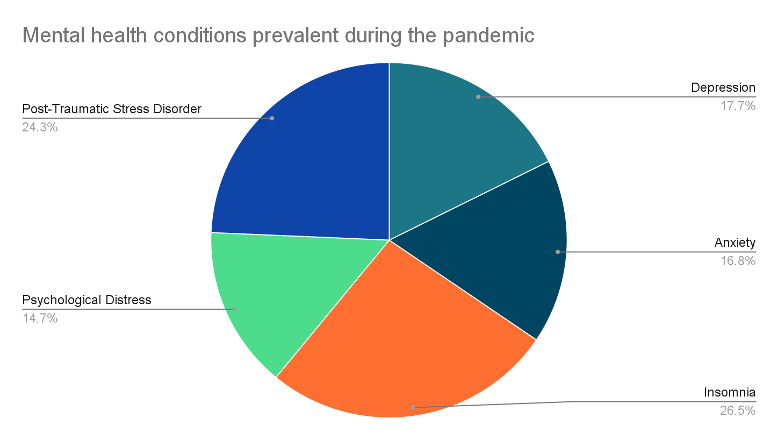

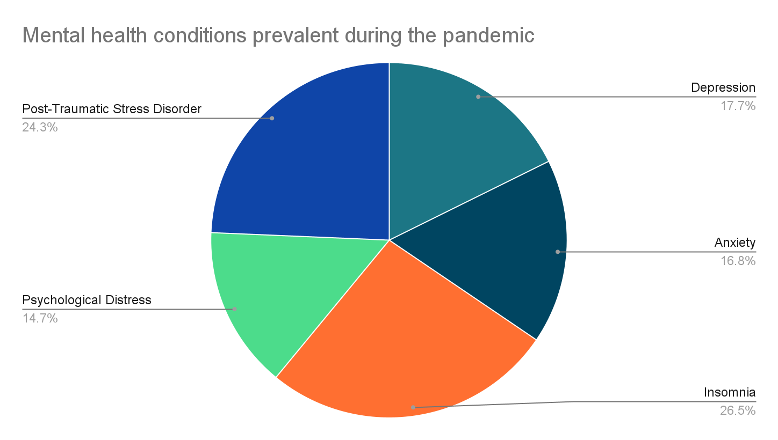

Insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety were the top four mental health conditions seen during the pandemic according to a study released in November. This conclusion resulted from the meta-analysis of 55 peer-reviewed journals conducted by the research team.

A study conducted March to April 2020 also identified an increase in acute stress and depressive symptoms in the United States, and found that people with preexisting mental and physical health diagnoses experienced these symptoms more than those without.

Bronzeville-based psychologist LaSonda A. Wilkins-Hines made similar observations of the Chicagoans she treated. Wilkins-Hines said she most often diagnosed patients with clinical anxiety and clinical depression. She held appointments via telehealth and did not take on new patients during the pandemic.

Wilkins-Hines, whose patients are predominantly African American, said she saw anxiety and depression peaked with the police brutality protests last summer.

“That’s when things really made a heavy turn in my practice,” Wilkins-Hines said. “What I was seeing was a lot of people feeling uncertain, unsafe, confused, angry, feeling that hopelessness and helplessness.”

Gardens that blossomed

Community gardens across the city reported increased participation during the last two summers.

Sarah Dugan, program facilitator for the city’s Community Gardens in the Parks program, said in an email, “Anecdotally, there was a big increase in inquiries for garden plots during spring and summer 2020, which seems to have tapered off to more typical levels this year.”

Prior to last summer, the Maxwell Street Garden in the Near West Side typically had a waitlist of five people, according to Tess Kearns, a board member and gardener there.

“Last year, we had a waitlist of 30 people and we had 15 plots available,” Kearns said. Apartments in the area with pool decks or community outdoor space closed those amenities last summer to prevent the spread of COVID-19, she said.

“There were a lot of people who didn’t get plots, but were desperate for the ability to be outdoors,” Kearns said. “This year, our waiting list was 47 people.”

To manage the increased interest, Kearns said they adopted a Friends of the Garden program during the pandemic to invite volunteers to work on the community plots and take home some produce in return.

The Maxwell Street Garden became a place for participants to “clear their heads,” Kearns said. “A lot of the stories [from last summer] revolve around just wanting to be outside after the mayor shut the lakefront down. Last year was really hard.”

Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot closed Chicago’s lakefront beaches from Labor Day weekend of 2019 through Memorial Day weekend of 2021 to reduce the spread of the coronavirus, according to a press release. The Lakefront Trail opened for exercise and transit with limited access and strict oversight June 2020; the status of the Riverwalk and 606 was similar, according to Block Club Chicago and NBC Chicago articles.

“We were like, ‘We’re going to the garden because it’s the one place you know you can be safe,’” Kearns said.

At the El Paseo Garden in Pilsen, volunteer coordinator Paula Acevedo said they increased programming in response to “a spike in attendance.”

“The space has been well-used during the pandemic,” Acevedo said. “A lot of people were really dedicated to the garden. … People were saying the space kept them sane.”

“It takes a village. It’s beautiful to be that conduit and platform for the community,” she said.

Health benefits of spending time in nature

A growing body of research illustrates the positive impact of spending time in nature on mental health.

A study released January 2020 identified that spending two hours in nature per week created significant health benefits across age, gender, and geographic differences. The study broadly defined nature and emphasized that the two hours was a cumulative tally.

Richard Louv coined the term “nature-deficit disorder” in 2005 and has since authored several books on the health benefits of nature.

“Any green space will provide benefit to mental and physical wellbeing, so it mainly depends on individual preference,” Louv said in an email. “More importantly is the frequency of those experiences. Connection to nature should be an everyday occurrence.”

A 2017 study offered a list of the top impacts of spending time in nature based on an extensive review of existing research: reduced stress, better sleep, reduced depression and anxiety, greater happiness, and reduced aggression.

Different nature-based activities can impact the body in various ways. Wilkins-Hines shares her nature-based advice with patients based on the mental disorders being treated. In her practice, she focuses on clinical anxiety and depression, stress reduction and relaxation, and Reiki, where she said she “manipulates energy to foster healing.”

For patients with depression, “the [activities] that are most impactful are ones where you’re getting the sun because that’s going to improve your mood,” Wilkins-Hines said. She said the sun provides vitamin D that boosts serotonin, the “happy hormone.”

“If you’re feeling suicidal and you’re feeling like you don’t belong, I encourage grounding techniques: to walk barefoot, to plant flowers, to plant vegetables – anything where you’re in the dirt and you’re bringing life to something,” Wilkins-Hines said. “You cannot change your way of thinking about the beauty of life [in a better way than] watching something grow into something, being responsible for the life of something.”

Wilkins-Hines said the impact of gardening extends beyond a specific physiological response in the body.

“I think these community gardens afford people that opportunity to come together and share stories and to build interpersonal relationships, to network and to just give a sense of family, give a sense of connectedness. And all of that is beneficial for mental health,” Wilkins-Hines said.

The impact of nature and gardening on mental health has been known to many for years and prior to the pandemic.

Kearns said she started to garden around the time she and her husband began the process of separation.

“This is my happy place,” Kearns said. “This was the place that I could just go and kind of forget about it. … I feel like it’s nourishment for your soul.”

Gardening can also help seniors and veterans, according to Acevedo, who said seniors are El Paseo garden’s largest demographic.

While the pandemic may have intensified certain health conditions for seniors, Acevedo said gardening helped their exercise, mental health and, for those who spent time gardening in earlier years, memory loss.

Acevedo also said the garden helped seniors feel less isolated, something the pandemic exacerbated.

“Even their own families were afraid to go see them. They didn’t see their children and grandkids,” Acevedo said. The garden added most of its new programming to benefit seniors, she said.

Acevedo said an Afghanistan War veteran joined the garden from Naperville, a 40-minute drive away, to volunteer his construction skills.

“He said, ‘I’m on disability. I don’t work. I need to keep busy, or I’ll lose my mind,’” Acevedo said.

Kearns said she thinks younger people have an easier time talking about mental health than older people. “Everybody may be just as anxious, but nobody’s talking about it,” she said.

Louv advocates for children and families to spend more time in nature through his nonprofit organization, Children Nature Network, to benefit all aspects of health within and beyond the context of the pandemic.

“Ironically, the coronavirus pandemic, as tragic as it is, has dramatically increased public awareness of the deep human need for nature connection –– and is adding greater sense of urgency to the movement to connect children, families and communities to nature,” Louv said.

“Today, nature connection can be one way to heal psychological trauma of the pandemic. Not a panacea, but one way,” he said.