Mary Oakey/Unsplash

Mary Oakey/Unsplash

The morning was soaked in the blistering sun. Families were gathered across the Motts Run Reservoir Park in Fredericksburg, Virgina. — some are learning how to use a fishing rod for the first time, and others are excited to get into bright red and yellow kayaks. Children squealed as volunteers from the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources hooked sticky and wiggly worms onto their rods. One seven-year-old boy caught a small blue catfish on his second try. Parents stationed in the parking lot called for them to slather on thick sunscreen, however even the beaming sun could not hold them back from the day.

It was a Saturday morning. Community members gathered around Abel Olivo, the executive director of Defensores de la Cuenca, a nonprofit also known as “Watershed Defenders.” He and his team had a special mission that day: to bring people to the water. The event, which was called Dìa de Pesca Familiar, or Family Fishing Day in English, took place where the water glistened under the heat.

Defensores de la Cuenca — also known as Defensores — focuses on connecting Latinos and Spanish-speakers through shared experiences within the Chesapeake Bay watershed. A Latino-led organization co-founded in 2020 by Olivo and Herlindo Morales, Defensores’ programming highlights the intersection of culture, environmentalism, and Latino communities across the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia.

“I wanted to create an environmental organization that really hit on something I thought was missing and that is the investment in the [Latino] community,” Olivo said. “My focus is to concentrate on those opportunities to enhance and build community level capacity so folks can address issues in their own lives.”

Defensores is one of the many community organizations across the Bay that prioritizes minority voices, but they are one of the few organizations in the area that specifically focuses on Latino communities.

Abel Olivo“We chose the word ‘watershed’ [cuenca] because it was a concept to try and understand that you don’t have to live near a body of water to have an impact on that body of water.”

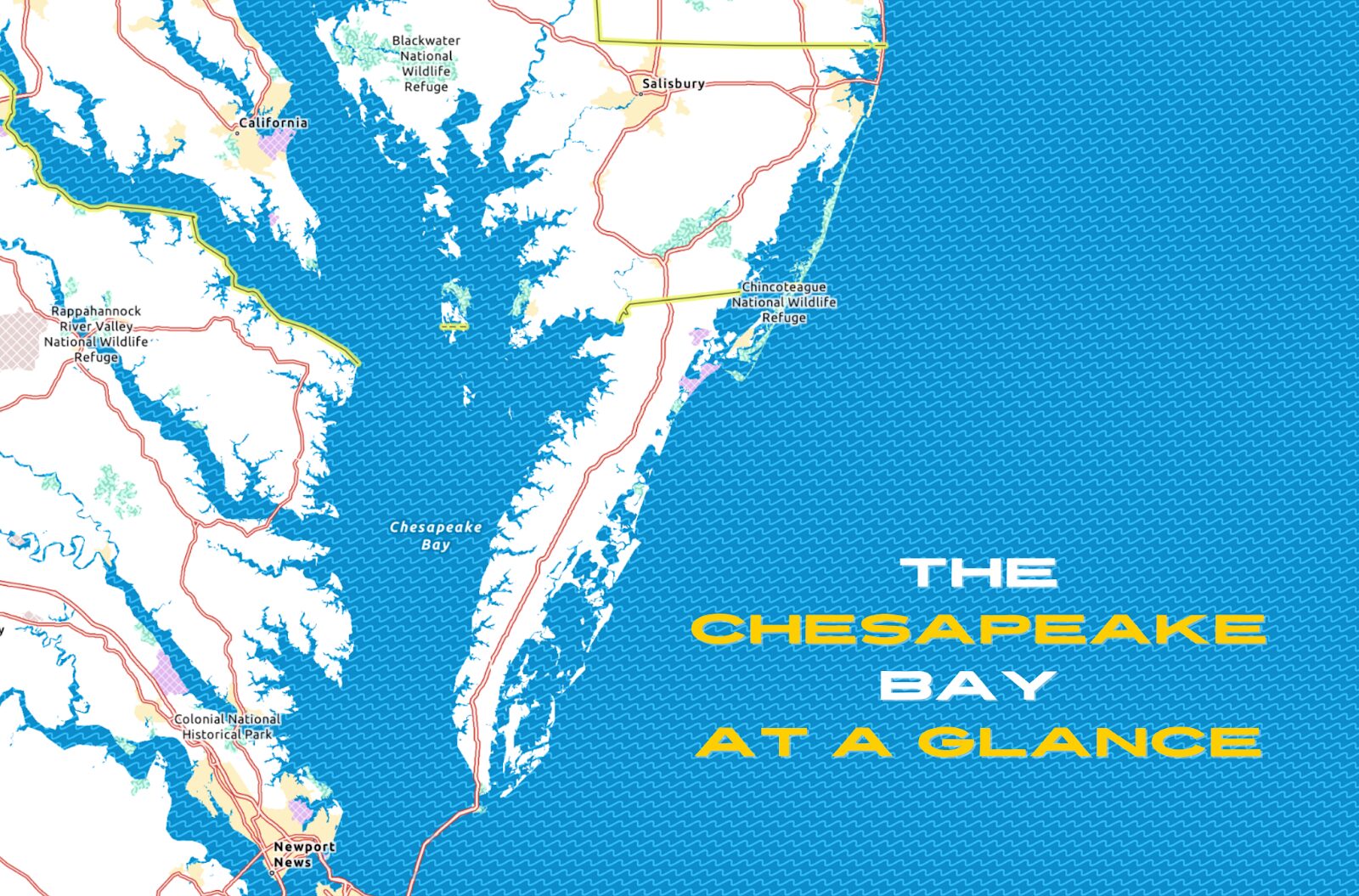

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States extending over 200 miles across six states: Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.

Also known as the Chesapeake Bay watershed, the geographical region can be defined as a “land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt to creeks, streams, and rivers, and eventually to outflow points such as reservoirs, bays, and the ocean,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The vast nature of the Bay encompasses a landscape inhabiting over 3,000 species of flora and fauna, with the Atlantic oyster and blue crab recognized as some of the most iconic species. The Bay’s biodiversity expands across vibrant communities rich in culture, family, heritage within the Mid-Atlantic region.

After a 12-year career lobbying for environmental advocacy on Capitol Hill, Olivo reflected on how he wanted to do something different. A former stay-at-home dad for four years, Olivo looked to create a new outlet for Latino voices to learn and grow through his nonprofit.

His passion for the environment led him to create a tree planting ambassadorship program, environmental focused youth groups, and an adult watershed education academy. He and his team believe through this they can foster a stronger relationship between Latino communities and the watershed that surrounds them.

For many families, an event like Día de Pesca Familiar marks the first time they have ever been on the water together. However, the charge behind Defensores’ programming is not only to sprout memories of fun in the sun, but inspire a blossoming branch of an eco-conscious and diverse community — Latino-focused stewardship in the Chesapeake Bay.

“I think that historically speaking, we as a community as Latinos, Latinx, Latinas have been left out of new opportunities,” Olivo said.

He believes in the community’s ability to become greater environmental stewards of the watershed, transitioning to not only be “recreational participants but also as people who can contribute and also lead others to do the same.”

Members from Defensores shared that linguistic isolation, funding opportunities, and watershed accessibility are some of the stark barriers standing in the way of Latino communities’ involvement in watershed restoration and advocacy.

By creating these unique spaces for learning and action, Olivo and his staff of eight are teaching a neglected demographic how to combat environmental injustices and champion for a cleaner, more accessible Chesapeake Bay.

The majority of community members involved with Defensores do not speak English fluently. And a greater majority do not prioritize environmental work in their professional or day-to-day lives, said Johanna Guadardo, programs coordinator for Defensores.

“One super important conflict is the language access barrier. A lot of the stuff that we need is not translated into Spanish. So, people can’t access those resources,” Guadardo said.

A former member of the Chesapeake Conservation Corps, Guardado is now planning monthly outreach events with the nonprofit including river trash cleanups, community gardening, and a city tree keeper program. However, the issue of communicating environmental resources is a greater obstacle. According to her, English to Spanish translations are hard to come by, especially accurate ones.

“For example, we see that a lot in Baltimore city,” Guadardo said. “To become a tree keeper you need to do workshops and training and it is all in English, nothing is in Spanish. So even if the community wanted to be tree keepers, there is no way because you need to know that language.”

When it comes to translating environmental work into Spanish, Defensores utilizes interpretive programming and multilingual instructors to host workshops for community members.

At a July event in St. Michaels, Maryland, they translated instructions during a water monitoring lesson taught by ShoreRivers, a nonprofit based in Easton, Maryland.

There, participants with Defensores learned three methods of manual water testing throughout the day.

Suzanne Sullivan, director of education for ShoreRivers, reflected on the importance of diversity within environmental education and outreach. She was one of the three instructors at the workshop.

“Making sure that our organizations hire and have diverse representation goes so far in bringing other communities into our work and us being introduced to their work. So I definitely think making sure our work reflects the communities that we serve goes such a far way,” she said.

Both organizations worked closely together to translate the activity in English and Spanish. Olivo later reflected that highlighting inclusion, language, and fun were central to engaging community members.

“If people don’t feel like they can go and participate and understand, then why even bother? Language is a really basic factor that is inhibiting participation.”

Abel Olivo

According to the National Park Service, over eight percent of the 18 million residents across the Chesapeake Bay watershed are of Hispanic or Latino descent.

Outreach events, like water monitoring with ShoreRivers, are fundamental for Olivo to carry out his mission of reaching this population. However, funding for transportation, food, and event programming is expensive.

Types of grants vary across the Chesapeake Bay region from education to watershed restoration and assistance.

According to Jake Solyst, a web content specialist for the Chesapeake Bay Program, organizations like Defensores are perfect for grants that prioritize community-oriented progress.

“From the Chesapeake Bay Program’s perspective, it is all about finding those local community groups and giving them the resources they need to do their work, because it all aligns,” he said.

According to Olivo, successful grant applications are often only made possible by having access to higher education and consistent exposure to larger organizations.

“Because these [grants] are competitive, all the [reviewers] can make their decisions on is with what’s on paper,” National Park Service Chesapeake Gateways Director of Partnerships and Grants Eddie Gonzalez said.

In addition to possible networking limitations, completed grant applications sometimes don’t align with what reviewers seek.

In recent years, over $668,000 of Chesapeake Gateways’ funding has been awarded to Latino organizations, Gonzalez said.

Without organizations like Defensores de la Cuenca, “then there isn’t anybody out there speaking for those [Latino] communities and speaking for their needs,” Gonzalez said. “And it is hard for us and it is somewhat not the right place for us to be defining those needs for those communities.”

With the increase of resources supporting Latino-led organizations, Latino stewardship is looking as vast as the Bay’s horizon.

Although there are many more events to plan and grants to apply to, the current guiding Defensores is shaped by one goal: to challenge Latino communities to engage meaningfully with the watershed, and hopefully the Chesapeake Bay as a whole.

On that hot Saturday, as Dìa de Pesca Familiar wrapped up, children pleaded with their parents not to leave. Although fishing rods were being put away and canoes were slowly taken out of the water, families cheered for Olivo and his team.

Ice cold lemonade, sweet sticky donuts, and hearty apples laid on picnic tables as the event came to an end. A small raffle also took place where three lucky participants won a brand-new fishing rod to take home and maybe continue practicing what they learned on the water.

While the reservoir is a small pocket of nature when compared to the large size of the watershed as a whole, it represents a space for Defensores to do what they do best. By gathering members of the community, they are not only bringing people closer together, but closer to what connects the spirit of the Chesapeake Bay region — to the water.

Editor’s Note: Coverage of water stories is made possible, in part, by the Walton Family Foundation. The editorial content is determined by Planet Forward staff and students. We thank the Walton Family Foundation for their continued support.