When the Cameron Peak Fire raged over the summer, it was obvious that the air quality was not safe in Northern Colorado. But air quality concerns aren't always as visually noticeable. (Photo by Jennifer Clary)

When the Cameron Peak Fire raged over the summer, it was obvious that the air quality was not safe in Northern Colorado. But air quality concerns aren't always as visually noticeable. (Photo by Jennifer Clary)

Fort Collins, Colorado, residents are used to spending time outside. It’s inherently a “Colorado” thing—hiking across foothills, skiing down snowcapped peaks, spending a great deal of time in nature—it’s what Coloradoans do. These healthy exercise habits increase brain function, boost metabolism, and make us feel good. But there’s a downside to spending time outdoors when the air is thick with microscopic pollution particles. As the greater mountain west region rebounds from a catastrophic and historic season of wildfires, environmental health scientists urge everyone from recreators to professional athletes to pay attention to their local air quality—out of concern that these healthy habits could directly harm your health.

2020 has taught us that some of our deepest problems are the ones we can’t see. Through interdisciplinary efforts on behalf of the Center for Science Communication (CSC) at Colorado State University, we’ve begun to understand how we can protect ourselves from one of those invisible issues.

The up-and-coming center, housed in the greater Department of Journalism and Media Communication, has goals, action plans, and tools in place to combat these issues, just as the following studies portray. It’s truly revolutionary, in that such an assortment of individuals can unite efforts to better understand an aspect of our world. The CSC seeks to connect stakeholders across campus in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities to improve the science communication process. It’s a stimulating democratic approach—The CSC; a center for the people, by the people—to science, which will pay dividends to research for years to come.

Enter Zoey Rosen, the dark-haired and bright-eyed scholar, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Atmospheric Science (a unique combination of meteorology and physics), and a master’s degree in Public Communication and Technology from Colorado State University. She is currently in year two of her Ph.D. in Public Communication and Technology, with a focus on weather. Rosen is part of the social-science side of the equation to the CSC’s overall mission of effectively increasing awareness of science—communicating to general audiences how air-quality research is important through a NASA-funded program: The Citizen-Enabled Aerosol Measurements for Satellites (CEAMS) project. Headed by John Volckens, Mechanical Engineering professor and principal investigator, the CEAMS team combines diverse academic backgrounds to tackle issues of air quality.

“CEAMS is a citizen-science project,” says Rosen. “We are trying to see if the act of measuring air quality influences how we understand and think about the air from a day-to-day standpoint.”

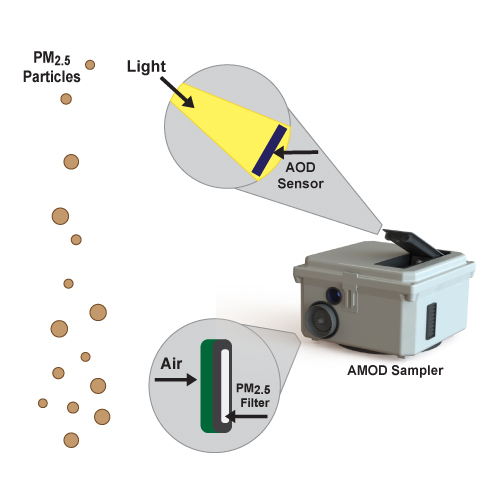

According to the CEAMS Blog, which has been managed by Rosen along with other CEAMS researchers, citizen science is the collaborative effort wherein volunteers help researchers collect scientific data. In many ways, citizen-science captures the goals of the CSC: bringing together academic experts, industry professionals, staff, students, and citizens to better coordinate science communication. Scientists at CSU have designed a machine that is sent to volunteers for setup in their backyards, dubbed the AMOD (Aerosol Mass and Optical Depth) sampler. See the diagram below for more information.

Why and how is CEAMS analyzing this data? Carefully, jokes Rosen. “We study how the air-quality measurements change over time, compare measurements at different locations, and assess how the existence of different types of particles can impact our health,” Rosen said.

Rosen illustrates how this can be tricky. Imagine when you were an elementary student, playing with magnets in science class. You might have been amazed when paperclips rapidly stuck to the poles, or transfixed by how two equal polar ends of magnets would simply refuse to connect. That science was understandable, tangible…visible!

“Can we apply that same sort of hands-on learning to adults in communities? That’s what we’re trying to do,” Rosen said. “Because most of the time, we can’t see if the air quality bad or not. We have no concept of how this actually affects us—it’s just air!”

When I see snow outside, my instincts tell me to tread lightly; I don’t want to slip. But I can’t see air, so how am I supposed to know when it’s bad? According to the World Health Organization, air pollution is one of the leading causes of death across the globe. It worsens underlying cardiovascular and respiratory problems and has a host of short-term exposure effects when exacerbated by events like wildfires. According to the EPA, the overall health effects from pollution lay on a spectrum, where the least significant effects are associated with large particle exposure for a minimal amount of time, and the direst effects are jointly associated with fine particles and longer exposures. This spectrum consists of relatively minor coughing and phlegm build-up effects, to bronchitis and asthma, finally progressing to heart failure, stroke, and premature death.

These statistics are courtesy of the World Health Organization.

Rosen explains how the importance of incorporating social sciences—or the human element, as she calls it—is extremely important in making sure that society understands an issue in science. Increased engagement with AMOD devices not only provides feedback about air-quality across the nation, but indicates a profound devotion to science.

“We ask questions at periodic stages throughout the deployment. If you’re measuring air quality for 8-10 weeks, then we give you a questionnaire before you start, one about 4 or 5 weeks in, and then one when you’re done and send your machine back,” says Rosen.

Anthropomorphizing—or ‘humanizing’—the situation itself has provided more opportunity for social science to analyze public motivations to contribute.

“We’ve found that participants get kind of connected to their boxes” (The AMOD devices). “When these boxes don’t work, it bothers them deeply,” chuckled Marilee Long, co-investigator within the CEAMS study, and health and science communication expert for the CSC. “In fact, Zoey and I are studying how citizens anthropomorphize the box.”

Long and Rosen are interested in assigning names, interaction opportunities, and even ‘wake-up-procedures’ into these AMOD boxes—altogether creating a more human experience for volunteers. Imagine your AMOD-upgraded morning routine: you brush your teeth, eat a bowl of cereal, and get ready for work, as Paul, your friendly patio AMOD, concisely tells you all the pertinent information about the air. Long predicts that this human element would promote a huge uptick in motivation to learn, to record data findings, and altogether understand air quality.

But CEAMS’ efforts aren’t alone in these studies; Long and Ashley Anderson, both members of the CSC and instructors within the JMC department, join this broad effort to teach, strategize, and improve the science communication process through a multitude of studies.

“Social science is really hard to do well, because people are complex,” Long paused, acknowledging the tricky power in that complexity. “It’s challenging to get people to give you their unadulterated thoughts. But when they do, it not only improves our understanding of a study—it motivates those citizen-sciences to want to learn more.”

Those unadulterated thoughts are pivotal to researchers like Long and Anderson, as they serve to provide authentic insights into how society views public health problems. Recently, the CSC has examined organizational framework approaches to implementing citizen science, as described by Anderson and Long’s involvement with Volckens and the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering.

“The project is in a bit of a holding pattern due to the pandemic, but it’s an integral part of the larger set of projects going on in the Center for Science Communication,” Anderson said. The project, an implementation of air pollution monitors called UPAS (Ultrasonic Personal Air Samplers, courtesy of Volckens’ company Access Sensor Technologies), is key in understanding the effect airborne chemicals have on at-risk individuals, such as firefighters.

With AMOD devices dispersed to willing volunteers throughout the nation by CEAMS, UPAS technology providing accessible air pollution sensors to literally inform individuals the quality of air they’re breathing, and social scientists examining attitudes and motivations to contribute every step of the way—the CSC has clearly gathered all components of academia necessary for a comprehensive analysis of air quality. These efforts summarize a greater goal of the true mission of the CSC—coordinating a diverse collection of personalities, backgrounds, and interests into one body. The CSC acknowledges that science can be challenging to understand, especially so with misinformation, social media, and, well, statistics—lots of statistics.

Jaime Jacobsen, JMC Assistant Professor and Emmy Award-Winning filmmaker (specializing in science documentaries), heads this center and its goals of pursuing research-driven strategies for understanding and improving the science communication process. She explains the value in turning charts, numbers, and data into concrete information that’s easy to understand.

“As science communicators, we are uniquely positioned to use narrative storytelling, visual metaphors, and analogies, which stem out of the latest research surrounding the science of science communication, to help inform and inspire the public to engage in the pressing issues of the day. I’m thrilled that the CSC will take a lead role on spearheading innovative collaborations across the sciences, social sciences, and humanities at CSU in order to further this goal.”

If science communication can foster more awareness about air quality…then would humanity begin to start making decisions for the betterment of their health? That’s the hope, argues Long.

“It’s similar in a way to smoking. A single cigarette is not good for you—similarly, a single day of bad air is not good for you. Would that single day cause problems for you?” Long pauses, peering out at the smoke-filled skies for a moment. “No, probably not…but it’s the cumulative effect that is directly impacting our health. People must start thinking about better times to exercise or opting to stay indoors when AQI measurements are too high.”

Those cumulative effects described by Long might best capture the role the CSC plays in public education on air quality, as well as other public health problems. As long as the CSC continues consistent teaching, mentoring, training, and outreach efforts amongst its studies, society will undoubtedly reap motivational and educational benefits.

Looking onward, researchers like Long, Anderson, Rosen, and countless others working in tandem with the CSC will continue their motives to understand and communicate the invisible, until we collectively progress toward less pollution-related death, less environmental tragedies like the ongoing wildfires, and perhaps most importantly—a greater appreciation for science.