Hayden Randolph

Hayden Randolph

In August 2025, a great hammerhead shark was found dead off the coast of Southeast Florida with only a hook in its mouth to explain.

The 11-foot, 4-inch predator seemed to die from a system of catch-and-release or sport fishing.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists great hammerheads as an endangered species due to their high incidental mortality with fisheries as well as their prized fins. With a slow reproductive rate, great hammerheads are distinctly vulnerable to these practices. There are currently no specific initiatives to conserve great hammerhead populations.

However, Cameron Ainsworth, Ph.D., a professor at the University of South Florida College of Marine Science, does not believe that this animal was targeted.

“I find it hard to believe that anyone is targeting hammerhead sharks intentionally,” he said. “I imagine what happened is that it was caught incidentally.”

Lori McRae, Ph.D., a biology professor at the University of Tampa, agrees.

“Most likely, the folks that hooked the great hammerhead originally were not trying to hook a great hammerhead,” she said.

Unfortunately, the damage to this vulnerable species was already done.

“Hammerheads are notoriously poor survivors after being hooked,” she said, “whether it’s on a longline commercial scenario or it’s by a hook-and-line recreational angler.”

Although this is just one example of a shark affected by recreational fishing, the threat to shark species globally is widespread.

A report by the Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science titled Catch Evaluation of Shark Fishery of South-eastern Australia mentions that hook size and shape could affect catch. However, trawling, the process of towing a net along the ocean floor to capture a specific species, presents the largest issue: by-catch.

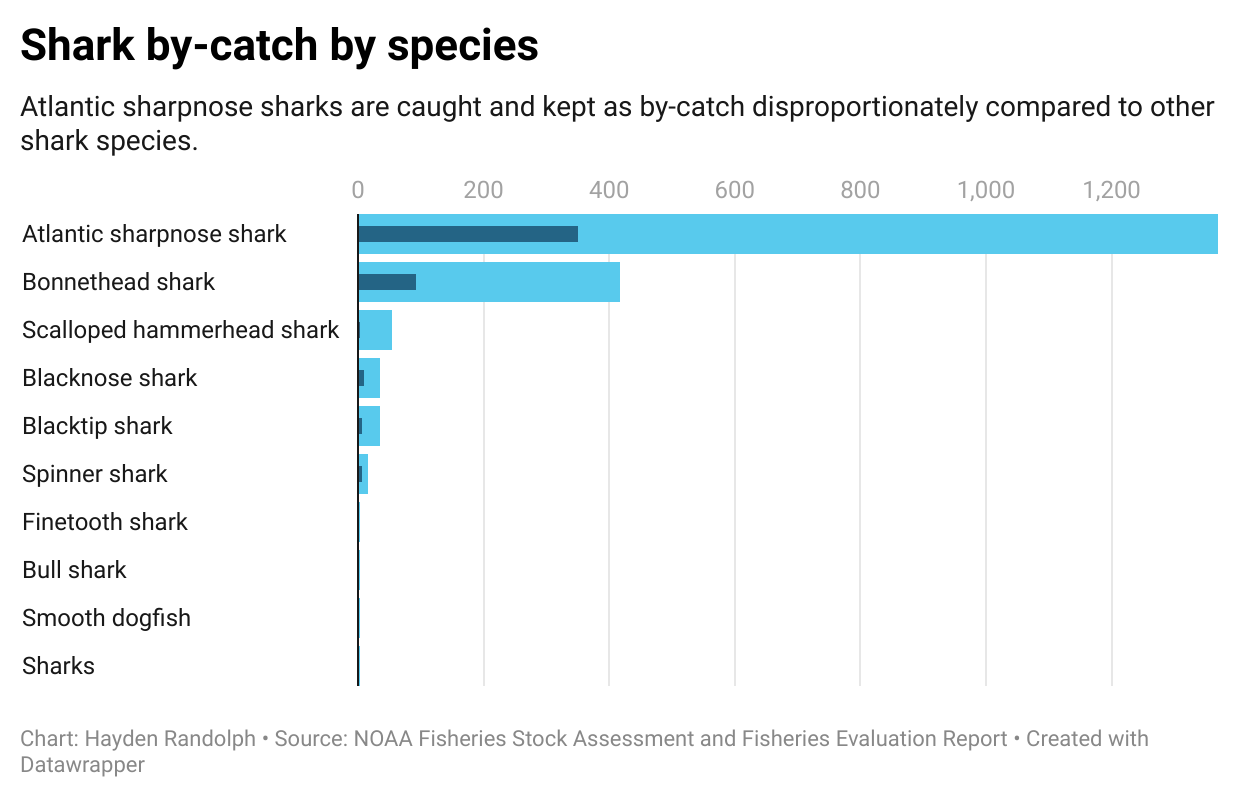

Daniel Huber, Ph.D., chair of the environmental studies department at the University of Tampa, explained the problem: “By-catch is the process through which a fishery targets a particular species because it has some economic value, but then incidentally catches other nontarget species,” he said.

A study published by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Journal of Marine Science in 2000 detailed that several shark species are particularly at risk, because they are seen as valuable for their fins. Consequently, when sharks are accidentally caught in industrial fishing lines, they are ultimately kept and killed because they are seen as profitable.

The Shark Research Institute writes that shark finning by way of longline fishing is responsible for the largest number of shark losses globally. According to McRae, this problem may pose a disproportional risk to hammerhead species.

“They have been a historically favored species in the finning trade because their fins are so large,” she said.

However, there have been legislative attempts to fix this issue. The Shark Fin Sales Elimination Act of 2019 would have made it illegal to sell, possess, or purchase a shark fin in the United States. While the bill failed to pass the Senate, it was later passed as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Undoubtedly, shark finning poses the largest threat to shark species. However, Huber explains that catch-and-release fishing is not without risk.

“You get up in the north and, pretty much, everything that is caught is released and survives,” he said. “Down here, you’re lucky if it’s 50/50.”

According to Huber, this difference is largely because of warmer water temperatures worsening the effects of physiological stress.

“Most sharks need to swim in order to breathe,” Huber said. “If their muscles are so fatigued that they are unable to sort of move themselves through the water, then they can’t get the carbon dioxide out of their gills.”

This build-up causes respiratory acidosis, due to carbon dioxide creating carbonic acid in the circulatory system and leading to the acidification of the circulatory system.

However, Huber acknowledged there is no simple solution to this problem.

“Interacting with any type of biodiversity facilitates an appreciation for that biodiversity,” he said. “You never want to say don’t go fishing.”

The advice he gave was to follow fishing regulations, including size, catch, and season limits. When asked what people can do to help sharks, Huber gave a simple answer.

“Don’t eat shark fin soup.”