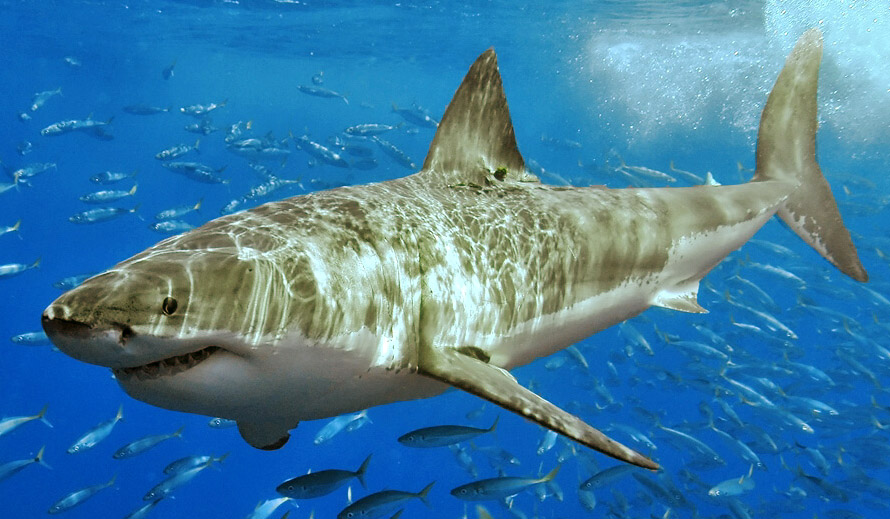

(Terry Goss/Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:White_shark.jpg)

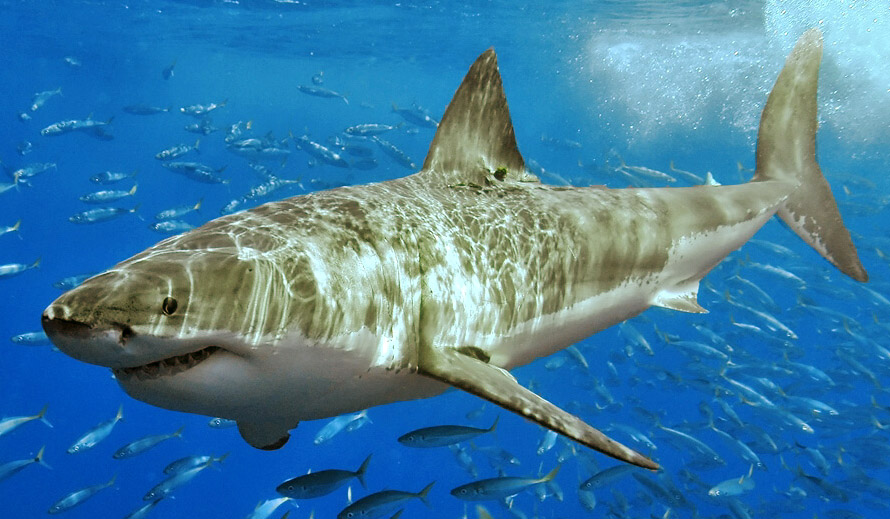

(Terry Goss/Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:White_shark.jpg)

Sharks have captured public curiosity long before Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws,” but are average beach-goers a key piece in this iconic species’ conservation? Scientists seem to think so.

Volunteer researchers, more commonly known as “citizen scientists,” are everyday people who lack formal training in scientific fields yet contribute to scientific work. Citizen scientists, now more than ever, are volunteering and collaborating with university research labs and government agencies, like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), by assisting with data collection and field research.

Shark scientists rely on the use of citizen scientists for data collection to monitor population growth and habitat shifts. Local citizen scientists notice something’s amiss and contact the appropriate agencies and facilities. For example, Californian citizen scientists noticed an influx of juvenile white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in bays and along beaches within the last several years as their coastal waters warm. These juvenile shark populations were observed much further north than usual.

Salvador Jorgensen, a research associate at the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, recently co-authored a paper in the journal Scientific Reports on this range shift of juvenile white sharks. The Monterey Bay Aquarium led the research, and Jorgensen and colleagues incorporated data that citizen scientists gathered.

Juvenile white sharks are endotherms. They need to stay in water that is warm enough to maintain their core temperature but not too warm to elevate it, Jorgensen explained.

“I kind of call it ‘The Goldilocks Zone’ for juvenile white sharks. It’s between 60 and 70 degrees [Fahrenheit],” he said.

Juvenile white sharks were mostly found in the warmer waters south of Point Conception, the headland where the Pacific Ocean and Santa Barbara Channel meet, according to Jorgensen. This is considered the point that separates southern and central California. However, during the 2014-2016 North Pacific marine heatwave, juvenile white shark sightings reached unprecedented rates in central California. Despite the marine heatwave ending five years ago, juvenile white sharks are still spotted along central California beaches.

Kisei Tanaka, a research marine biologist for NOAA and lead author of the paper, said that the primary source of their data came from online open-access databases where people can use a website or phone application to take photos of a plant or animal for identification and upload the information to free public sources. Scientists may even have the latitude and longitude of the species sighting if someone geotagged the uploaded photo with the exact location.

Tanaka and Jorgensen looked at the public access databanks along the California coast over the last five years to confirm the uptick of juvenile white shark sightings further north of Point Conception. Then, marine scientists conducted their scientific survey expeditions looking for juvenile white sharks. The public access databanks utilized, like iNaturalist, allowed the scientists to pinpoint which areas appeared to be the most juvenile white shark heavy, based on citizen scientist sightings.

“This [method of data collection] is very novel and effective in terms of capturing the change in the species distribution that weren’t affected by the scientific survey [our research team conducted] but may be able to be conducted at a much more local scale by more participants,” said Tanaka.

Through the research described in their paper, the shark scientists determined that juvenile white sharks are moving poleward as their initial nursery ranges, like south of Point Conception, are too hot for their temperature-sensitive bodies. While rising ocean temperatures have been a concern to marine scientists for years now, citizen scientists quickly caught the attention of researchers with the influx of juvenile white sharks spotted further north and submitted to these databases.

“White shark is a very charismatic species that a lot of people pay close attention to, and they happen to be the one that responds to the climate very abruptly,” said Tanaka.

Tanaka discussed how sharks tend to capture the eye of the public which makes them one of the best species to use as a flagship for conservation initiatives regarding climate change. The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species categorizes white sharks as “vulnerable” and were last assessed in November 2018.

Chelsea Black is a Ph.D. student studying marine conservation at the University of Miami’s Shark Research and Conservation Program. As the Shark Satellite Tracking Coordinator, Black monitors all their satellite-tagged sharks and verifying that the transmissions are accurate. She also works as the Adopt A Shark Program Manager. If someone donates the amount of a satellite tag, Black assigns them their “adopted” shark. The donors can then name the shark and create an origin story of said name. The donors can then check up on their tagged shark at sharktagging.com.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Black’s lab actively engaged the public to try more hands-on citizen science by having designated days where groups, such as corporate organizations or students on field trips, go on their boats and help with shark tagging. During these expeditions, citizen scientists get to measure sharks, attach a satellite tag to sharks, take a biological sample of a fin clip and write down field data. They even hold special expeditions where they take young girls out for tagging events with an all-female crew. The program is called Females in the Natural Sciences (FINS), and the goal is to excite young girls about shark science and demonstrate that science needn’t be a male-dominated field.

“It’s really cool seeing people come out on the boat with us who sometimes have never been on a boat, have never seen a shark. We will have people who are, you know, kind of afraid of sharks or are not sure what to expect, and by the end of the day, everyone is just like, ‘That was so amazing! I didn’t realize how calm sharks are.’ They’ll see us handling the sharks, obviously very safely, but without fear of the shark harming us,” said Black.

For Black, changing people’s opinions on sharks while contributing to scientific data collection is one of her favorite parts of working with the Shark Research and Conservation Program. She believes that informing and engaging the public in citizen science is crucial for shark conservation.

“We’re losing sharks at such a significant, you know, percentage each year that it will be in our lifetime that we will see species go extinct,” said 27-year-old Black.

According to Black, if you look at the data, there was a massive spike in shark killings after “Jaws” came out in 1975. However, the rise in concern over sharks led to more shark research facilities. After over forty years of adverse publicity, white shark perceptions are finally changing for the better.

Christopher Lowe is a professor of marine biology, co-author of the juvenile white shark research paper, and has worked as the Director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach since 1998. Lowe said that for the first time in years, he feels hopeful about shark populations returning thanks to conservation initiatives. He feels that people are genuinely excited about protecting and celebrating sharks.

“I would argue that sharks are now as much a part of our [American] culture as baseball and the Fourth of July,” said Lowe.

Lowe believes conservation citizen science is growing because people are interested in “reconnecting with nature.” According to Lowe, some people want more than seeing a piece of nature at face value but to learn something about it.

White sharks are “apex predators;” they reside at the top of the food chain. They prey but are not preyed upon, and they remain a crucial part of oceanic ecosystem conservation by keeping all the other levels of the food web in check. If the apex predators disappeared, the ecosystem’s natural balance would fall. Lesser predators would grow in population thus until their prey was depleted, leading to mass die-outs. By protecting white sharks, whole ecosystems are being sustained.

“If we are conserving ecosystems and we’re interested in health of the ocean, for example, we should be concerned with the health of all the species from the smallest, lowliness of phytoplankton all the way to its top predators,” said Jorgensen.

With the popularity of a range of volunteer monitoring growing, marine scientists are feeling cautiously optimistic about the future. Many shark species are returning to the American coasts. But for marine life, current conservation efforts may not be enough if the symptoms of climate change continue to worsen.

“It’s going to take the planet. It’s going to take everybody, and that is a bigger challenge,” said Lowe.

The research says that if sharks, and marine ecosystems as a whole, want to persist, humans have to combat climate change. Shark populations are shifting and reacting to people changing the planet explained Jorgensen. As ocean temperatures continue to rise, it is up to humankind to save sharks from extinction.