Agriculture’s intersection with art and science

On a peaceful summer evening in California’s Central Valley, there’s not a cloud in sight. There hasn’t been in weeks. Fields of tomatoes, almonds, sunflowers, corn, and melons line the highways and snaking irrigation canals. Farmers here count on the rain to stay away.

20 miles west of Sacramento, a woman walks her dog down a dirt road in the twilight. They walk past a 22-acre organic farm on UC Davis campus. The dog doesn’t sniff out the jackrabbit nibbling grass in the vineyard, but the rabbit hops away when a Volkswagen pulls up. Jorge Berny, a postdoctoral scholar, hops out and starts to prune a row of tomato plants on the student-run farm, hoping to finish while there’s still light in the sky.

Not far north, there is a very different scene on the Schreiner Farms, which is well over 100 times the size of the student farm at 15,000 acres. A combine scrapes a field of dead sunflowers from the earth. With a growl, the towering green tank collects the seeds and hurls most of the plant out the back; fertilizer for next year’s crop. A few miles away, a tomato harvester picks up a stream of the red fruit, leaving behind a wake of pancaked green plants.

Schreiner Farms is a conventional operation. They use varieties of crops genetically modified with modern breeding techniques. Researchers at places like Bayer’s R&D farm carefully breed varieties for specific purposes such as disease resistance, size and taste. Conventional farms are also free to use synthetic fertilizer and ten varieties of genetically engineered crops.

The vast majority of food Americans eat daily comes from conventional farms. Organic farms only cultivate 1% of U.S. agricultural land, and the rest is considered conventional. Organic farmers play by a different set of rules. They cannot plant genetically engineered plants, and they must use natural fertilizer. The result is a product that some view as more pure, and that in most cases was produced in a more sustainable way.

Raoul Adamchak, the UC Davis professor in charge of the student farm, says that organic farmers could benefit from being allowed to use some genetically modified organisms. He says most of all that conventional farmers could learn a sustainability lesson from organic growers. Organic and and genetic engineering may not need to be enemies the way they have often been made out to be.

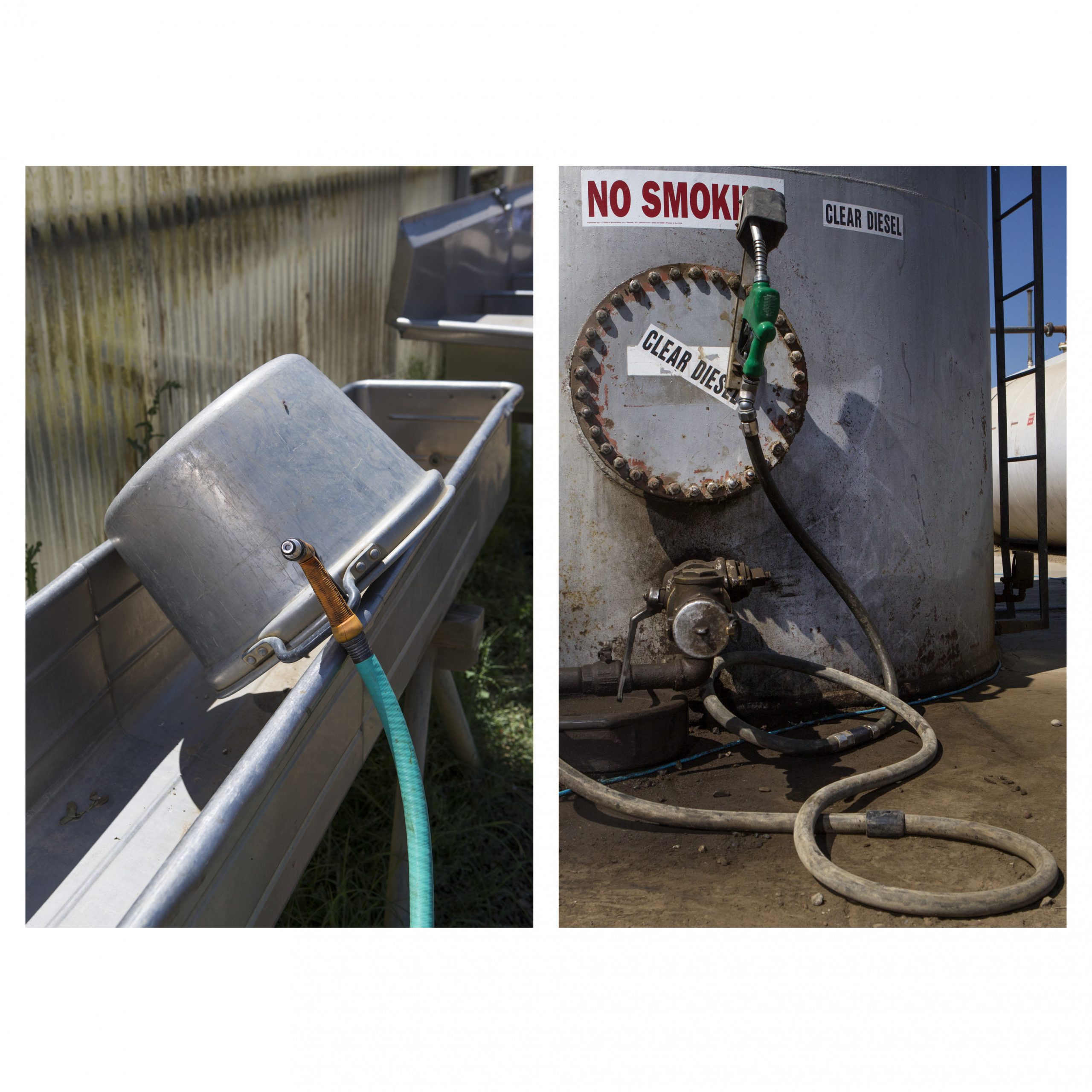

In these diptychs, I compare six scenes from the organic student farm with scenes from Schreiner Farms and the Bayer’s R&D farm, both of which I associate with conventional farming.