Tyler Hickman

Tyler Hickman

Mason jars filled with hundreds of thousands of seeds line the shelves inside a small house in Boulder, CO. Nearly every seed has been touched by a farmer at MASA Seed Foundation, meticulously cleaned, examined, and counted before being stored. At MASA, this small team of farmers works throughout the year, often seven days a week, to grow organic, bio regionally adapted crops. Unlike other farms, MASA rounds out the process by saving these seeds to be preserved for the next season.

MASA is taking their practices back to the age before industrial farming, when saving a harvest’s seeds, sharing, and trading them in the community was normal. But as populations grew and farms scaled up, the industry transitioned to genetically modified seeds, bio-engineered to withstand blights, resist toxic pesticides that otherwise would kill the plant, and maximize the yield and nutritional value. As the industry focused on crops designed for mass production, nearly 90% of crop varieties in agriculture were lost according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Genetically modified seeds are often not adapted to specific climates, but they are many farmers’ most reliable source for production. This precipitous drop in crop diversity has created an uncertain and fragile future for agriculture, one that MASA is hoping to provide an answer to.

“In 1929, 1930, before the first hybrid, everyone would be doing exactly what we do. We’d be like, ‘Oh yeah, we save a part of the crop for seeds’,” said Laura Allard, the seed house and operations manager at MASA. Before production agriculture was the norm, farmers would trade and share seeds from that year’s successful crops, fortifying a network of seeds adapted to grow in their local environment.

Today, farmers can simply log into an online store and with a few clicks, add seed varieties from all over the world to their virtual shopping cart. For a commercial grower who’s focused on one crop, like corn or soybeans, these genetically engineered seeds help strengthen the chances of a fruitful harvest. But many of these seeds are patented by companies like Bayer and Syngenta, making it illegal for farmers to save the seeds to plant next season and forcing farmers to repurchase new seeds at the start of every season.

This leads to a dangerous homogeneity among available seeds that fails to take advantage of the resiliency inherent to a diverse population. Seeds are like little nuggets filled with data, and by selecting for certain traits farmers can help a crop adapt to their environment overtime. “Whatever that season was like, whether it’s maritime or dry, windy, whatever happens, those seeds have the knowledge of that in the face of inevitable extreme weather or climate changes,” Allard said.

MASA’s founder Rich Pecoraro has been breeding and adapting seeds for over 40 years. When he founded the non-profit in 2019, he donated his entire collection, which now holds more than 1,000 different crop varieties. These seeds’ genetics hold decades of knowledge, and are slowly adapting to Colorado’s unique growing conditions.

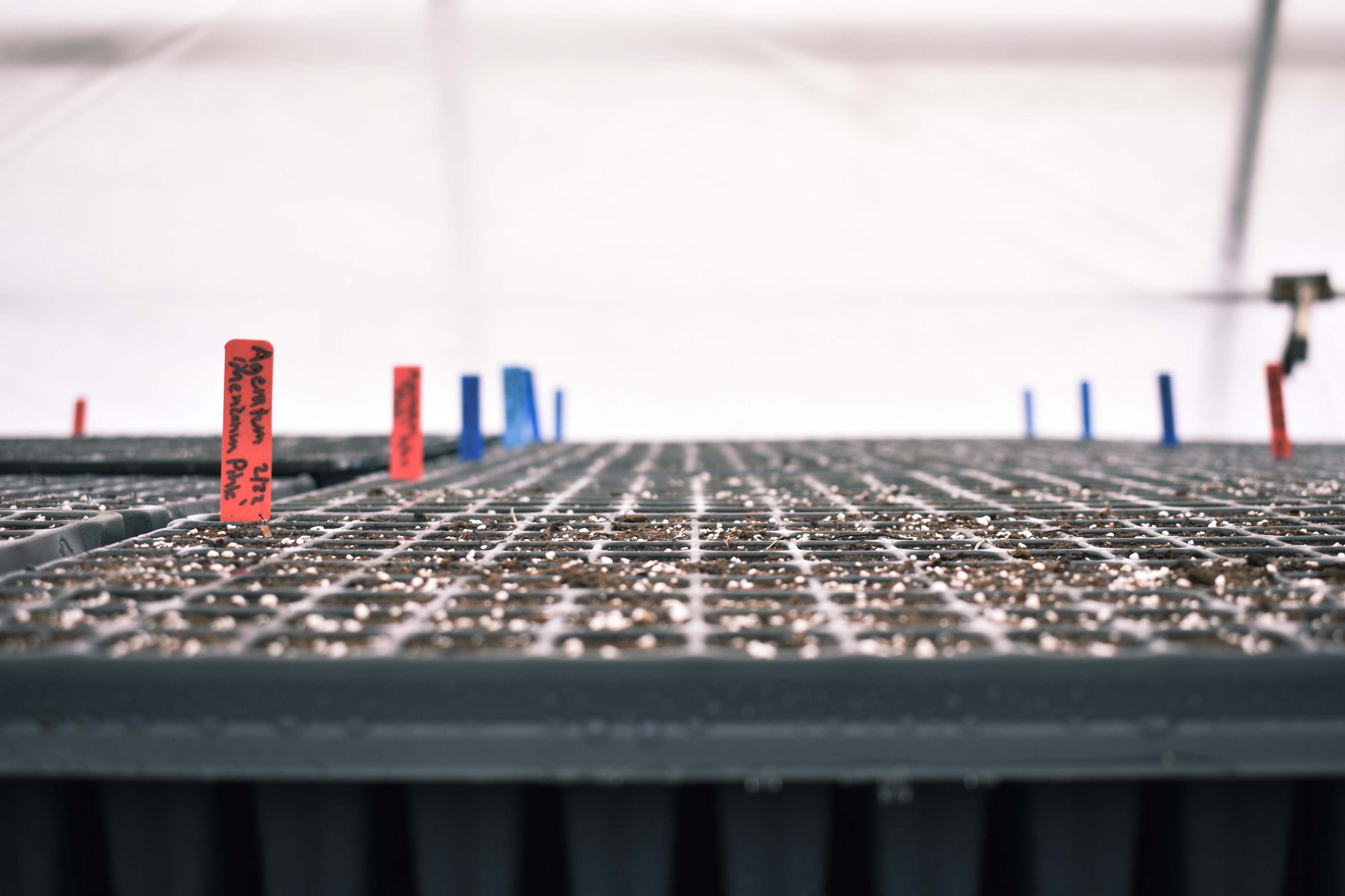

During springtime on MASA’s 24 acres of land, greenhouses are beginning to overflow with the seedlings of hundreds of different plant varieties. Leafy stems of ‘Billy Buttons’ craspedia wait patiently to sprout yellow globelike flowers, and soon the squat stalks of ‘Green Zebra’ tomato plants will blossom and don yellow and green striped fruits like ornaments.

Each plant sprouts from a seed, and nearly each seed has been touched by one of MASA’s farmhands. The work is meticulous and time consuming, from harvesting seeds the size of pencil tips to the hours spent misting carpets of green seedlings that cover greenhouse benches end to end.

For MASA, these seeds are sprouting more than just stems, they’re contributing to a sustainable vision. “We never pictured just being on this project, six or seven of us, working as hard as we can to get the next crop of seeds,” Allard said. While research and breeding are central to MASA’s mission to build a bio regionally adapted seed bank, the ultimate goal is to educate.

If they don’t teach the importance of seed preservation, then this knowledge will only exist within the confines of the farm, Allard explained. One of MASA’s next big steps is to launch their Thousand Petaled Seed Cooperative. MASA would share seeds with community members, from novices to commercial farmers, for them to grow, adapt, and learn about seed preservation.

“We have to free ourselves to be able to find time or bandwidth — capacity is our word — to launch a mini ag campus for people to learn how to grow seeds, to be inspired to do it,” Allard said.

MASA is a piece of a global movement to return to seed farming and build a more climate resilient agricultural system. University of Colorado Boulder professor Nolan Kane points out that MASA is unique in its scale. “It’s not a huge place,” Kane said, but in terms of the number of varieties they’re growing successfully, it’s special. “It’s not just cultivating something familiar. It’s doing that but also trying to generate something new.”

While industrial agriculture places constraints on seed sharing and negatively impacts biodiversity, there is still a place for it, according to Kane. “It certainly has provided very stable, high nutrition food for a huge population reliably,” he said. At the same time, there’s value in agriculture that focuses less on monoculture, and more on a genetically diverse community of plants.

Biodiversity in farming can lead to a more robust ecosystem. If one crop variety is affected by blight, or can’t successfully adapt to a changing climate, it’s failure won’t decimate an entire food system. Applying ideologies from MASA and other seed sharing organizations can create a new approach to large scale farming, Kane said.

For Kane, it comes down to “thinking about how to improve agriculture by both adding in alternatives in different ways to predominant agriculture, but also, how can we improve the way that we do large scale agriculture? Those are both things that I think you can learn a lot from here by just seeing how they do things.”