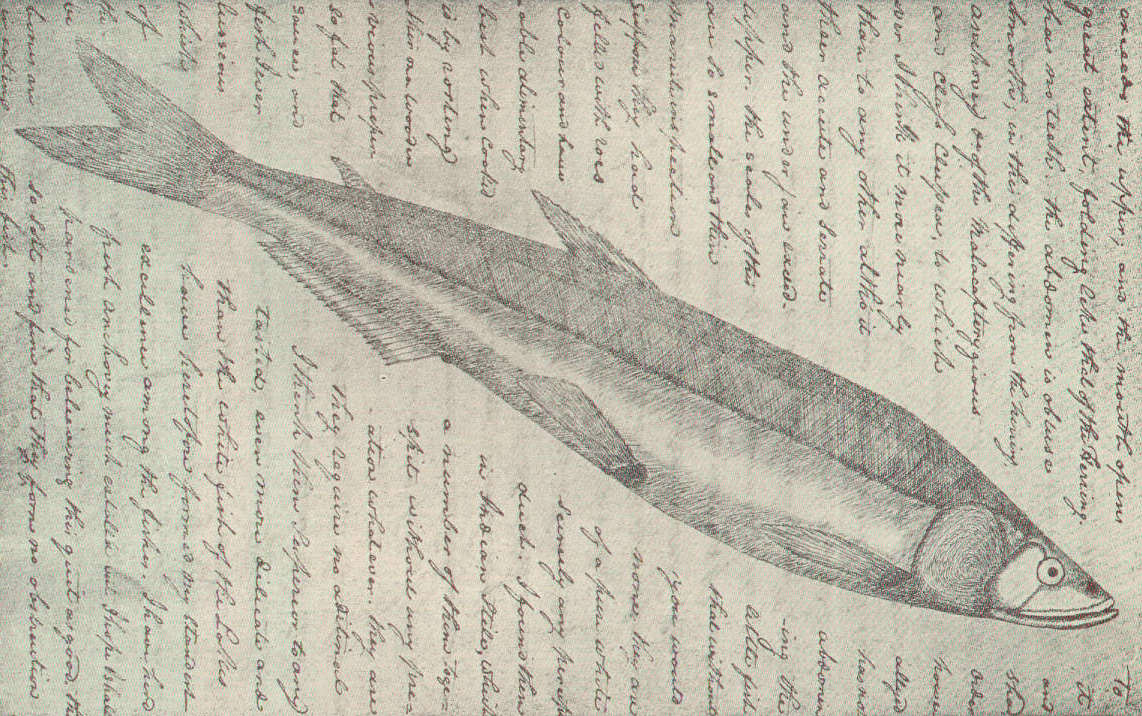

Sun-dried candlefish, also known as hooligan, eulachon, and oolichan. (Brodie Guy/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

Sun-dried candlefish, also known as hooligan, eulachon, and oolichan. (Brodie Guy/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0))

In today’s fossil-fuel-powered world, the importance of oil seems obvious –– it’s everywhere from our polyester clothes to our Tupperware to our heating systems.

However, people’s use of oils came before we had engines to burn them. We have always chased fats for their energy.

Before my Lindblad Expedition trip to Southeastern Alaska, I subconsciously saw oil as something unnatural and something always damaging to ecosystems and to our own health. I now see oil as just another resource that industrialized societies have exploited and reaped in excess. The way we go about searching for energy, though, can vary from disastrous to or harmonious with nature, and we are at a crucial point in our atmospheric timeline to relearn old and sustainable ways of energy harvesting.

The revelation began with my introduction to candlefish. On our second day in Alaska, I joined a tour of the Chilkat Valley. With its pristine water and air quality, it is home to the latest salmon run of the year and is thus where eagles congregate in the fall.

Chilkat Valley is aptly known as the Valley of the Eagles for its yearly visit of up to 3,000 eagles that decorate the trees like ornaments. Living below the soaring eagles in this part of Southeast Alaska are the Tlingit people who have been able to maintain their artistically expressive and resourcefully subsistent culture. Historically, with all that their environment had to offer them, there was enough time for woodcarving, tapestry-weaving, and storytelling.

“They have so much candlefish that the river turns black during their run,” our naturalist yelled over the bus engine and rattling windows.

My ears perked up at that new fish name.

“Hooligan is another name for candlefish, and it is so dense with oil that once it’s dry, it can be lit like a candle,” he continued. The Klukwan clan gathered enough of the candlefish and traded the excess with the nearby Abathascan peoples, establishing trade routes that were known as “grease trails.” This oil allowed them to light their homes and communities, as well as store food for up to a year in the oil. The fish itself also offers people half of their daily caloric needs due to the lipid density. Agutuk or Akutaq was even a pre-freezer ice cream made of hooligan oil, berries, and fresh snow for people in Western Alaska. The Tlingit people who would procure the hooligan oil would mostly use it themselves to preserve berries, such as highbush cranberries, blueberries, and salmonberries, year-round.

The fish and its oils provided light, food preservation, and nutrition for people. The grease from the fish is high in unsaturated fats and provides more vitamin A, E, and K than other sources of fat. Even Meriwether Lewis, of Lewis and Clark, stumbled upon it during his travel and journaled that it was “superior to any fish [he] ever tasted.” With so many benefits and uses, I was amazed I had never heard of this fatty fish. Hooligan, however, remains a prized possession only to Alaskans. Because hooligan is primarily found in Southeast Alaska, it was not a resource that is known to outsiders and was never harvested on a large scale.

Later that day, back aboard the National Geographic Sea Lion, we spotted and watched a humpback whale join us at the surface. It was bubble-net feeding, creating a tunnel of bubbles in which plankton and small fish would be trapped. Then it swam with an open mouth through the middle and burst through the surface. In 2022, it was captured only in our photographs, but if it had been 50 years ago, the spotted whale would have been hunted down. Since whales are found in all of the world’s major oceans, they are a prized and sought-out source of oil.

Between the 18th and mid-19th centuries, oil lamps across the United States and much of the Western world required oil extracted from whale blubber. While in Inuit cultures, whaling is a culturally, spiritually, and materially significant tradition, American whalers went out to sea to harvest profitable carcasses. From when they first arrived to the North Pacific in the 1830s, the American whalers over-hunted the waters. And by the 1940s they had pushed north into the Bering Sea. They were primarily after bowhead whales, since each yielded 100 barrels of oil whereas sperm whales averaged only 45 barrels of oil.

In addition to the blubber oil, bowheads also provided bristly baleen, of which the baleen plates were cut and filed into corset fixtures, fishing rods, or buttons. The oil was used for lamps, cooking, soap, candles, paint, and mechanical lubrication. Since whales provided so much raw material for luxury goods, there is a genre of paintings that glorify the whaling industry for the goods they produced.

Whereas subsistent cultures involve the whole community in the hunting, processing, and consumption of a whale, industrial societies left the hunting to the professional whalers, the processing to the factories, and consumption to the elite in societies.

The commodification of whale oil and baleen were devastating to their populations. In 1853 whaling became the fifth-largest industry in the U.S., where 8,000 whales were killed for the sake of commercial goods. About 20 years later, petroleum wells popped up on the West Coast of the U.S., providing an even more accessible and powerful oil.

The growth of the new oil industry didn’t correlate with an immediate decline in whale hunting. Petroleum-powered engines outcompeted wind-powered sails, and whaleships had a chance to become even more effective. The petroleum industry thus increased whaling efficiency before whaling would be officially banned in 1971.

Alaska’s first oil reserves were discovered in 1957, two years before Alaska was granted statehood. It was in 1967, though, that Alaska became known as an oil hub with the discovery of Prudhoe Bay’s oil deposits. Experts estimated there to be 24 billion barrels of oil, of which 12 billion have been recoverable and so far extracted.

But today’s oil flow is slowing. The petroleum flowing through the 800-mile trans-Alaska pipeline from Prudhoe Bay is estimated to be about a quarter of its peak flow in the 1980s. Not only does the petroleum seem to be slowing, but land sales and industry interest in the region seem to be dropping as well. Most recently, the Biden administration canceled the Cook Inlet lease sale which “would have opened more than one million acres for drilling.”

While this was met with contempt from pro-oil representatives and individuals, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has canceled lease sales in the region in 2006, 2008, and 2010 due to a “lack” of interest from the industry as well.

Having read headlines about Alaskan residents relocating towns due to the permafrost-dense soils melting below their houses and infrastructure, I thought all of the state’s residents would be eager to move away from fossil fuels. But while they are feeling the effects of climate change so directly and rapidly, Alaskan residents also directly benefit from the Alaska Permanent Fund. The fund provides an annual check to families that is a percentage of Alaska’s oil revenues, averaging a payment of $1,600 annually. Beyond fossil fuel money however, Alaskans can cut down costs by investing in renewables since they already pay almost double the amount citizens in the lower 48 are charged for utilities.

On that day on the Klehini River when I learned about candlefish, I also learned about a mining operation that has sprung up between Klukwan and Deishú (now known as Haines). Across from the river that is home to candlefish, salmon, and eagles, as well as the human residents of the valley, stands a shredded mountainside. Known as the Palmer Project, the mine provides copper and zinc to the metal-heavy electronics and energy markets. Here stands the frustrating reality of our industrial society. To continue feeding our energy-intensive lifestyles, we must source the energy from somewhere.

Europe and the United States were once fueled by local vegetable oil, before whales were hunted down in Alaska, and later abandoned for oil reserves there and abroad. Today, internationally, we are in an era of pushing past fossil fuels to reach mineral-intense electrification. Our air may be near free of fossil fuel emissions, but is it guaranteed that our soil and water will be free of leached minerals and chemicals?

With four years spent pursuing a bachelors in environmental studies at George Washington University, punctuated with my trip to Alaska, I continue to be skeptical of an industry-first approach to solving our climate crisis. This is where technological advances paired with profit are expected to spur change. As we’ve seen from how we’ve fueled our societies since the Industrial Revolution, it is damaging and unsustainable.

In contrast to phrases we hear in mainstream politics and media like “boost growth,” “revitalize the economy,” and “energy superpower,” the word we often heard in Klukwan and describing the Tlingit culture was “subsistence.” Through art, business, and architecture, even today the Tlingit people focus on the renewable and the regenerative. One Tlingit woman, Jodi Mitchell, founded the Inside Passage Electric Cooperative, which is an energy group that installs small-scale hydroelectric dams that use slow-spinning blades that small fish can swim through and large fish can swim around.

Mitchell started a renewable energy project that meets human desires and needs as well as those needs of surrounding animals and the land. Her work follows the increasingly renewable trend in Alaska, where its contribution to state-wide energy has increased by 25% between 2010 and 2019.

Across the state, with many Native Alaskan-run projects, we see solar projects saving their communities $7,726 each and dams safely built on salmon-rich rivers that plan to soon provide 90% of Igiugig’s power. Beyond the typical solar and hydro projects we often discuss in the lower 48, Alaska also now has biomass facilities that process wood or fish waste and kelp.

Humans, like all living things, need to take resources from the environment in order to survive. But like all other creatures, we collectively need to be more in tune with natural processes so that we don’t continue to strain our environments.

Einstein is quoted as saying, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” I deeply believe that we cannot solve an industrial issue with industrial methods. In this time of climate transformation and societal potential, we can use thoughtful technology on a smaller and more local scale to meet our energy needs. Not energy wants, but energy needs.

I think it’s time we ask ourselves if we need to hunt a whale when we can just stick with a fish.

––

Editor’s Note: Lindblad Expeditions, our Planet Forward Storyfest Competition partner, made this series possible by providing winners with an experiential learning opportunity aboard one of their ships. All editorial content is created independently. We thank Lindblad Expeditions for their continued support of our project. Read all the stories from the expedition in our Astonishing Alaska series.